Warda Yassin is a British-Somali poet born and raised in Sheffield. Having started writing in her late teens, Warda has grown immensely as a poet, and continues to do so. Her winning of the New Poets Prize in 2018 and her first pamphlet Tea with Cardamom (published by Poetry Business) are proof that she is someone to watch out for.

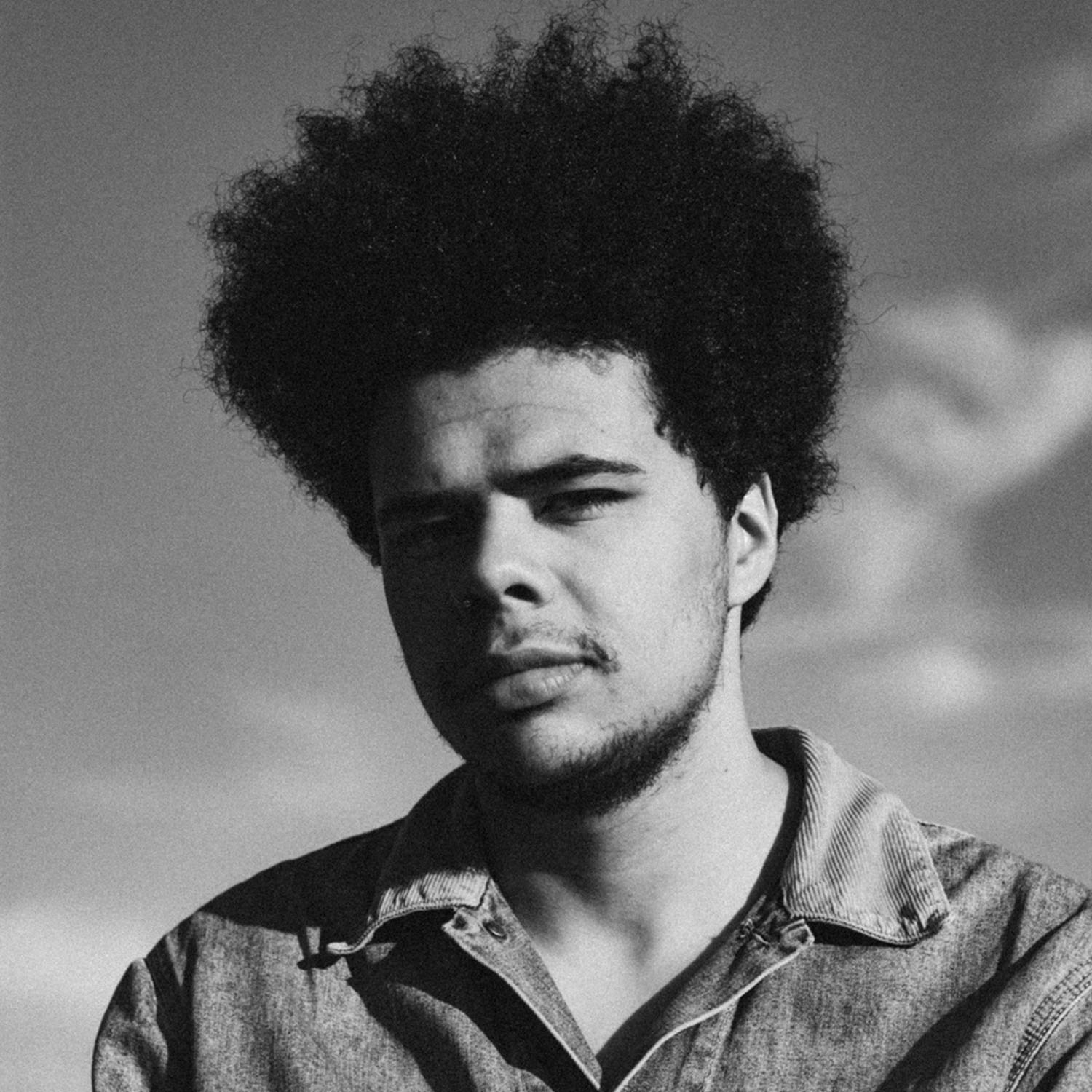

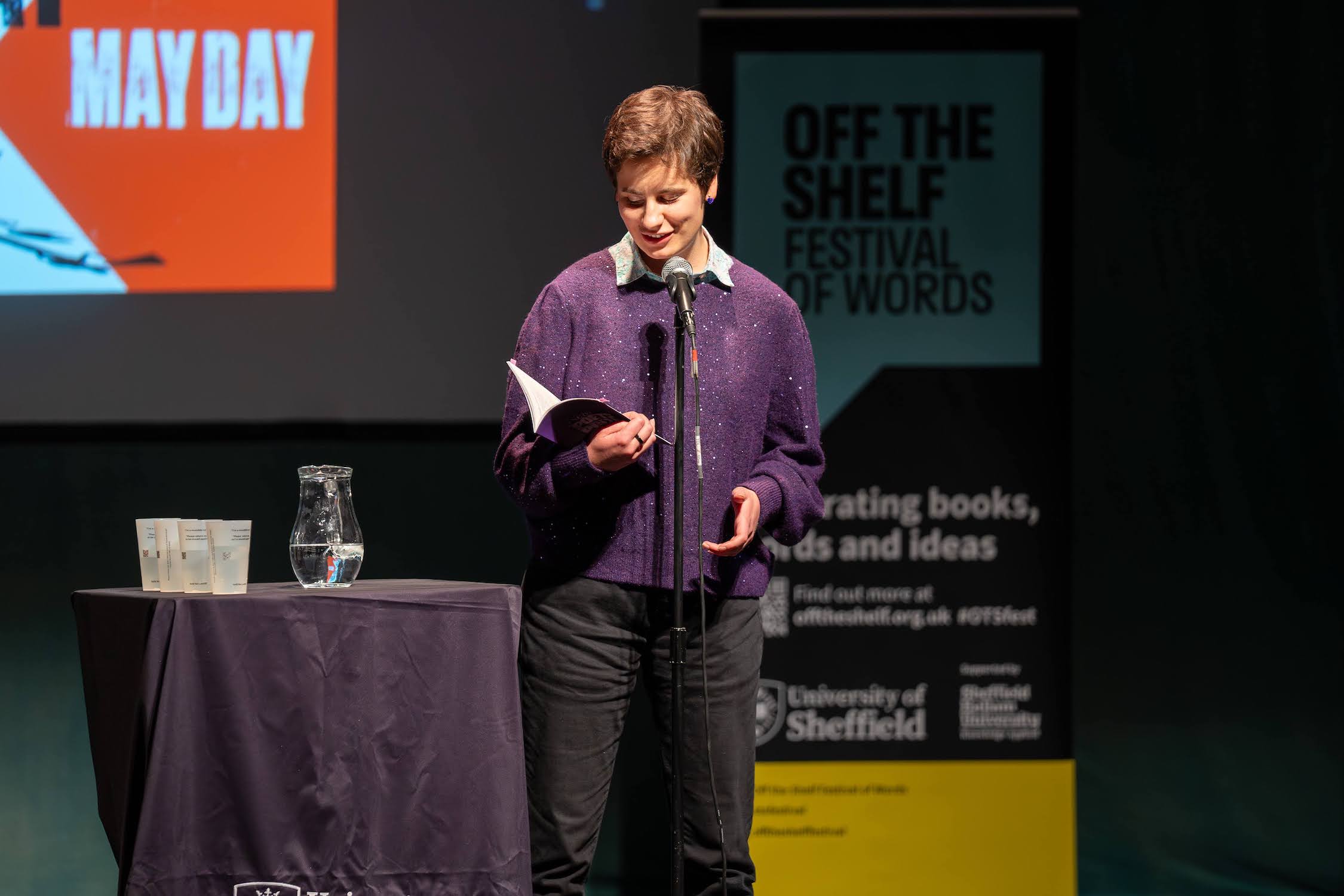

Warda is dedicated to her craft and wants to encourage young people to reap the benefits of writing. Whether it is through her work as a secondary school English teacher or through workshops with local writing groups like Mixing Roots (a group for young voices of colour – click here to sign up to September's workshops), Hive and Nyara, and discussions with The Lit Collective, Warda is constantly spreading her love for poetry. She is even in the running to be the next Sheffield Poet Laureate. [Update: Warda has now been confirmed as the new Laureate! She'll take over from the fantastic Otis Mensah at an Off the Shelf Festival event this October.]

With a warm and vulnerable writing style, Warda leaps over boundaries and challenges the minds of her readers. Her poems cover themes including heritage, womanhood, sisterhood, family, life – the list goes on. One poem that particularly resonates with me is ‘Cavendish Court’, published recently in DINA’s Small Pleasures Project online anthology. It describes her relationship with her grandmother, which I can connect to on a personal level. Warda’s poetry upheaves emotions that you may have had buried deep inside and forces you to confront yourself and allow yourself to feel these emotions deeply. Her personable attitude shines brightly in her poetry and in conversation.

Below is an edited version of my conversation with Warda where we discuss her journey into becoming a poet and everything that follows. She and I also bonded over our love of Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman and she recommended I check out the work of poets Roger Robinson and Warsan Shire and the book Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

Why poetry?

That’s a great question! For many reasons. Because there’s a stillness to it. It’s quite condense, it’s quite concise. I felt like I could talk about topics that were important to me, poetry gave me an outlet. I’m Somali and gabay is in our culture, which is a massive part of it. You don’t necessarily have to be literate in Somalia to be a poet – it’s a lot of spoken word, it’s quite a poetic language. My late uncle was a poet as well, and my mum wrote a poem when she was grieving. We perform poems at weddings. When I made the connection to it on a personal level it was when I was around 19 and I started going to a local girls’ writing group run by Hive founder Vicky Morris with a focus on mental health. It really created a safe, supportive and inspiring environment for me. I was really encouraged and given opportunities by Vicky, who is a force for young people and creative writing in Yorkshire. For the first couple of years I wasn’t writing with the end goal of publication, it was purely for the enjoyment of it. It was kind of a personalised archive I was doing of myself, my family and my wider community. I could capture something, a part of my history, and I found that beautiful.

Have current events such as lockdown and the Black Lives Matter movement inspired or impacted your creativity?

Things like the Black Power movement, as a Black Muslim woman, that is inevitably going to alter how I think, how I perceive things. Have I been writing about it per se? It probably finds itself within the work. There’s certain incidents that have moved me profoundly; I’ve been absolutely haunted by the death of Shukri Abdi last year. When I was younger my father was attacked quite close to our house, a racial attack, and lockdown has returned that to my psyche and that is something that I’ve been exploring creatively. I think Black Lives Matter is more than just creativity, it’s practical; sharing your voices and helping others out, speaking up. And the arts kind of add weight to that, though I think it’s a movement that is alive, that everyone can be a part of and vocalise and change.

How do your relationships with your family and friends play a part in your poetry? Your poem ‘My Sisters’ really touched me because I have sisters as well and our relationship is totally how you describe it.

It’s a very unique relationship, having sisters. Each set of sisters is different to each other and we connect in different ways. I didn’t think I was ever gonna show them, and in the end one of my sisters said, “you can’t not put that in the pamphlet!” They’ve always been supportive. My younger sister herself is a writer and my grandma will tell me stories specifically for me to write about. They're so sweet, there’s nothing that I feel I wouldn’t be able to say. The people that I know and that I love have always inspired me.

Is your connection to your roots important when writing poetry?

It’s a part of who I am, it’s where I come from, and that’s going to bleed itself into my work, into my psyche. But as a writer I should be free to explore and write about whatever moves me or inspires me. Sometimes I feel like I’m writing the same poem my whole life. I think a lot of people feel that way – you’re writing about the same things just in a different way, and there’s nothing wrong with that. At the end of the day, everyone’s writing about the same thing; people and life and love and grief and death, just through different layers or different angles.

Can you elaborate on the other things you’re interested in writing about? There’s some strong female roles in your poetry as well.

Definitely, I’m inspired by women. I’m inspired by my faith, by my homeland. I’m inspired by the diaspora experience here, and by growing up here as well; I was born in Sheffield and although my connection back home is strong, it’s tentative in the way that I didn’t grow up there. I’m interested in the country, the urban, the inner city, friendship, and more recently I’ve been looking at relationships. When I set out to write about them I wasn’t necessarily saying I was going to write about femininity or feminism or strong women. I was mirroring or capturing these women that inspire me – like in ‘Weston Park,’ my mother and my aunties are in that poem. So it’s unintentional but it’s intentional, if that makes sense.

That makes sense, you sort of reflect who you are because being a woman is part of your identity.

I also think it’s important to showcase vulnerability in women as much as strength, and their strength in vulnerability, in resilience. If we think about Black women in particular, there’s a perceived notion that there’s this strength. Of course we are strong, but that expectation of it can sometimes lead to dehumanisation. So I’m not afraid to show them in a vulnerable light as well.

I want to talk about your poem ‘Cavendish Court’. There’s one line that really resonated with me: “her arms are soft olive branches.” Could you explain that please?

That was one of the ones I wrote in the pandemic. It’s about my grandmother. With the pandemic and the vulnerability that old people have, I found myself visiting her and we would talk from the window, as many people in the country have. That poem is about the experience of that closeness yet that distance. My grandmother really struggled with me not coming in. There’s a lot of loneliness, I would say, in that poem as well. That’s a theme that’s finding itself more in my work and I think a lot of people’s work given the climate. I’ve been writing on dementia and Alzheimer's, which is something we’re dealing with in my family, and that element of when you grow old still having your youthfulness in you. I wanted to capture the playfulness and youthfulness of my grandmother as well, how ultimately she’s still a girl in many ways despite being the matriarch of the family and this powerful figure. This idea of extending an olive branch is exploring this idea of her telling me how things are at home. A massive part of our relationship is her often being the portal to what’s going on with our family back home, or our politics, or about the flooding that was going on at the time.

I’ve covered most of the questions that I wanted to ask. Is there anything you’d like to add?

The last thing I want to say is, I think all young people should be writing poetry. There is a place for them in poetry. They’ve just got to join their school library, join their school poetry group – there are so many grassroots organisations in most cities and communities. That’s why I run projects that help young people release their voice and their words in the way that I wanted when I was growing up. That’s what we need, it’s so inspiring and helpful.

- Words by

- Safiya